As seen in Wall Street Journal

Regional banks’ exposure to commercial real estate is more substantial than it appears

Bank OZK had two branches in rural Arkansas when chief executive officer George Gleason bought it in 1979. The Little Rock lender today has billions of dollars in commercial real-estate loans, including for properties in Miami and Manhattan, where it is helping fund the construction of a 1,000-foot-tall office and luxury residential tower on Fifth Avenue.

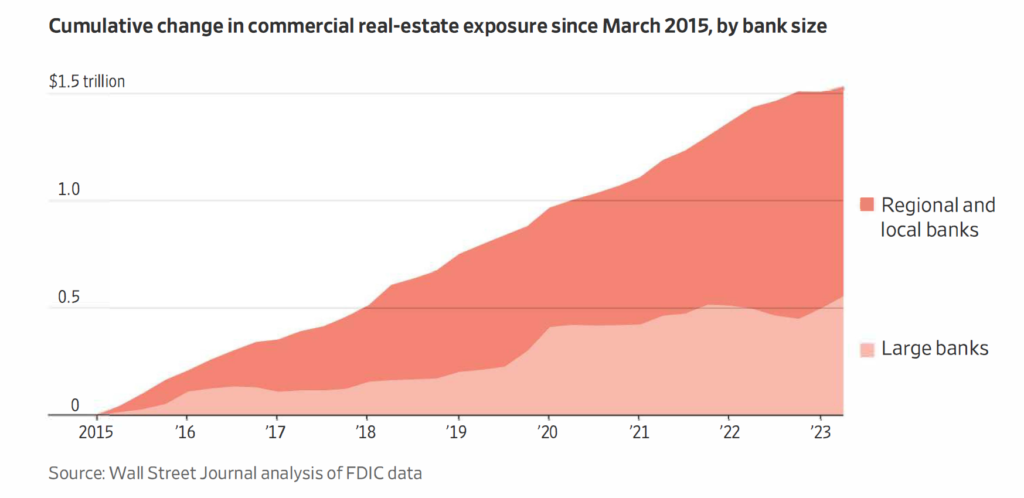

Regional banks across the country followed a similar playbook, gorging on commercial realestate loans and related investments in big cities over the past decade.

With the commercial real-estate market now in meltdown, those trillions of dollars in loans and investments are a looming threat for the banking industry-and potentially the broader economy. Banks’ exposure is even bigger than commonly reported. The banks are in danger of setting off a doom-loop scenario where losses on the loans trigger banks to cut lending, which leads to further drops in property prices and yet more losses.

Bank OZK hasn’t pulled back from lending, but it has started to see some signs of market trouble. In January, a developer defaulted on a roughly $60 million loan from Bank OZK after construction costs escalated, the bank said. The loan was considered relatively safe because it was far below the building site’s value of $139 million in 2021. In December, a new appraisal put the property’s value at $100 million.

The bank is effectively stuck with the property. “Buying land in the current unstable environment is not something that a lot of people will do,” Gleason, the CEO, said during an April earnings call. Bank OZK declined to comment.

Today’s troubled market, fueled by rising interest rates and high vacancies, follows years of boom times. Banks roughly doubled their lending to landlords from 2015 to 2022, to $2.2 trillion. Small and medium-size banks originated many of those loans, and all that lending helped push up property prices.

Bank OZK’s success over the years allowed Gleason to build himself a 27,000-square foot French chateau-style mansion in Little Rock, which he filled with a vast collection of European art. “I’ve never said that what we do is risk-less,” Gleason told the Journal in 2019. Still, he added, he considers OZK “probably the most conservative” commercial real-estate lender.

Over the past decade, banks also increased their exposure to commercial real estate in ways that aren’t usually counted in their tallies. They lent to financial companies that make loans to some of those same landlords, and they bought bonds backed by the same types of properties.

That indirect lending-along with foreclosed properties, trading portfolios and other assets linked to commercial properties-brings banks’ total exposure to commercial real estate to $3.6 trillion, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis. That’s equivalent to about 20% of their deposits.

The volume of commercial property sales in July was down 74% from a year earlier, and sales of downtown office buildings hit the lowest level in at least two decades, according to data provider MSCI Real Assets. When deals begin again, they will be at far lower prices, which will shock banks, said Michael Comparato, head of commercial real estate at Benefit Street Partners, a debt-focused asset manager. “It’s going to be really nasty,” he said.

Lending is the lifeblood of all real estate, and regional and community banks have long dominated commercial real-estate lending. Their importance grew after the 2008 financial crisis, when the country’s biggest banks reduced their exposure to the sector under scrutiny from regulators. Low interest rates made higher-yielding real-estate loans lucrative to hold.

That strategy now appears risky after the Federal Reserve raised interest rates. Banks are under pressure to pay depositors more to keep customers from fleeing to higher-yielding investment alternatives. Without cheap deposits, banks have less money to lend and to absorb losses from loans that go bad. Depositors withdrew funds from many small and regional lenders earlier this year after the collapse of three midsize banks stoked fears of a systemwide crisis.

The doom-loop scenario is starting to play out in big cities where office vacancies have soared. Real-estate investors that are unable to refinance their debt, or can only do it at high rates, are defaulting. The lenders, no longer getting the debt payments, often have to write down the value of those mortgages. Sometimes the bank ends up owning the property.

“The plumbing is clogged right now,” said Scott Rechler, chief executive of real-estate investor RXR. “And that is going to create a backup that will eventually overflow on the commercial real-estate markets and on the banking system.”

When Rechler asks banks to refinance his office loans now, few respond. In some cases, he said, it’s not even worth trying. Rechler had a $240 million mortgage coming due on a 33-story office building in lower Manhattan. Vacancies were high, renovating or converting the building would be expensive and the cost of a new mortgage was way up. He ran the numbers and decided to default on the loan. RXR said that it’s been working with the lender to market the building for sale to repay the loan at a discount, and that they have discussed possible loan modifications if the building isn’t sold.